Reality is complex and ever-changing, more of a process than a thing, a fluctuating quantum soup in its base layer (or so we currently think). To make sense of it, we need to simplify reality as we perceive it using models that highlight some, but hide other aspects. That way, in the wise words of John Law, we distort reality into clarity.1 This comes at a price. There’s a famous saying in statistics, attributed to George Box, that all models are wrong, but some are useful.

We use several terms to speak about how music life is organised and make claims, explicit and implicit, about what is valuable and meaningful about it. Talk of industries suggests an economic dimension while explaining music as scenes might emphasise the social and cultural practice aspect of music. The lens of an art form might raise to the fore the resulting artefacts – works of art, while the concept of an ecosystem draws on the metaphoric connection to the complexity and interconnectedness of the biosphere and underlines the dynamics of the many actors in the system. All these and other concepts are also being used for different ways of constructing political representation of the music world, or in other words, tell the stories of what music is, how it works, who is doing what and why it all matters to the society at large and to policy makers in particular.

In the paragraphs below I will aim to unpack some of the different words we use, such as “sector”, “industry”, “scene”, “ecosystem” and the different perspectives these offer.

The music sector

The “music sector” is probably the most widely used phrase to designate everything-to-do-with-music and for understanding most discussions we could leave it at that. If the phrase “statistical framework” makes you want to unsubscribe, please skip the rest of this section.

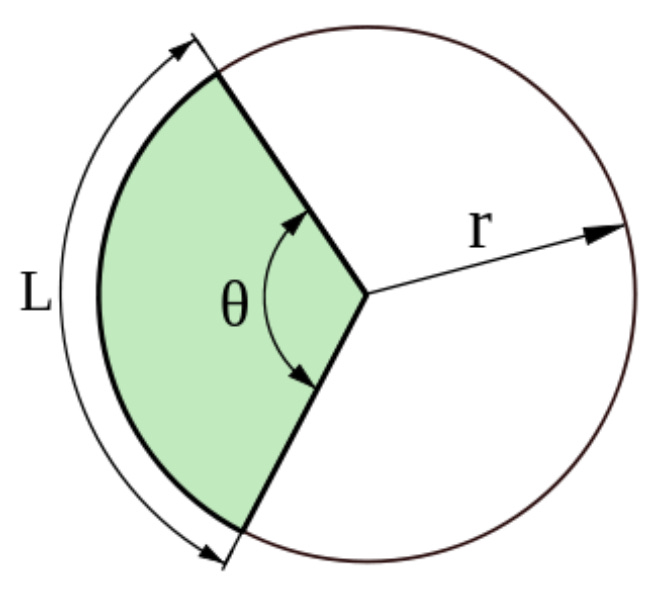

The term “sector” is used as a metaphor from geometry to denote a part of a (mostly circular) whole. Using the sector metaphor likely comes from economic and industrial organisation theories and is meant to categorise the different fields of human (economic) activities. In practice, sector and industry are often used interchangeably, while a more systematic use would always have sector as the broader term, comprising different industries.

From a policy making perspective, the commonly used framework for organising fields of activity into a system is the International Standard Industrial Classification of all economic activities (ISIC), governed by the United Nations Statistics Division. In the European Union, we have our NACE codes, the main classification system of Eurostat and used in all the Member States for national statistics, that is broadly aligned with ISIC. In the broadest sense, music is somewhere within the section of “Arts, entertainment and recreation” of ISIC and NACE, but actually it is a bit all over the place. There are many problems with these classification systems from the perspective of music and culture more broadly and that will merit its own series of blog posts.

In another, more thematic framework, The 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics, “music” is organised under section B. “Performance and Celebration”, but notes that “music is defined in this domain in its entirety, regardless of format. As such, it includes live and recorded musical performances, music composition, music recordings, digital music including music downloads and uploads, and musical instruments”2.

The above is relevant to know because even if we (from the music sector) will want to propose our own definitions and clarifications of what the music sector is, the policy making system, when making use of “official” statistics, its way of seeing the reality, will necessarily “see” the sector through such frameworks with all the ensuing problems. The emphasis will be on types of actors and activities that lend itself to exclusive classification and not on context-sensitive thick descriptions.

Music industries

According to a useful definition by Investopedia, an industry is a “group of companies that are related based on their primary business activities. [...] Individual companies are generally classified into an industry based on their largest sources of revenue”. Accordingly, it is most common to speak of the three music industries – the recorded music, music publishing and live music industries –, each corresponding to a main source of revenue, whether the sale and licensing of music recordings or author’s rights to musical works, or selling access to live performances. I have always found this inadequate as it clearly lacks a fourth kind of value and its set of revenue streams – the artist brand. The direct revenue streams from an artist persona brand might come from the sale of merch, brand deals or direct subscription fees from platforms that are built around following an artist instead of paying for access to (licensed) music (i.e Patreon). These are captured by artists, their management, or perhaps through so-called 360 deals by various kinds of music companies. However, we don’t talk of an artist brand industry (yet). Curiously, the most recent MIDiA report on global recorded music revenues introduces a new term “expanded rights”, referring to “labels’ revenue from sources such as merchandise and branding. In short: superfan formats”. However, it seems to me, there is no reason to presume that it’s always the record labels creating and capturing the value from artist persona and their superfan communities.

Industries can be explained through value-chains, referring to the steps needed to create a product and take it to market. Especially after the advent of the Internet and the Great Lowering of Barriers to Access brought on by many digital platforms (the actual degree of this lowering can also be contested), the processes of how music is created and reaches its audiences are truly diverse, complex and fluid and it could be argued that a classical firm-centric value chain analysis is not fit for purpose anymore.

In the past century, the recorded music industry was dominant and became increasingly consolidated, to the point of nearly becoming synonymous with the phrase “music industry” itself. It only takes a second to google a characterisation such as3:

The careless conflating of the recorded music industry revenues with the “size” of the music industry as such is rampant across digital press. At worst it’s the effect of a cognitive bias that Kahneman calls WYSIATI, or What You See Is All There Is4. In this case, the only thing one tends to see is the well-known and easily available IFPI Global Music Report.

The so-called recorded music industry is perhaps the most consolidated and organised of the three (or four) music industries – the major record labels as IFPI (representing the “recording industry”, a seemingly minute, but potentially important difference from “recorded”) and the rest, or so-called independents, as WIN globally and IMPALA in Europe (though the two latter are not confined to record labels only and rather position as representing independent music companies). These organisations are able to craft a coherent identity and narrative for the industry and the value it creates as well as complementing this with reports proposing to describe it through data and statistics. The Global Music Report by IFPI has become a staple over the past decades and few stop to reflect how accurate their stats and methodology might be.5

The sense that the recorded music industry IS the recording industry – the producers, mostly the record labels who invest and own the rights – seems prevalent. However, an actual value chain-based approach to the recorded music industry would have to include the distribution channels, both physical and digital. Thus, an economic evaluation of the recorded music industry – from creation, record production through distribution – would thus have to be broader. Yet no such regular and well publicised data portrait exists. A possible explanation is that given the natural frictions within the value chain, such as debates about whether the distribution of revenues from digital music consumption is fair, etc., there is no stable institutional arrangement for political representation that would prioritise a regular economic report on the full value chain of the recorded music industry.

The lack of a clear and well consolidated industry structure around capturing the artist brand value can be the reason we don’t even think of this as an industry – no one is telling the story consistently and compellingly enough, supported with the required statistical artefacts lending the needed legitimacy. Maybe it’s not needed for the artists and management, but for analysts and researchers, at least beyond the academic field, this seems like a blindspot.

The segments across the industries

To match the metaphor of a sector, I’m suggesting to use segments for ways of grouping and understanding certain music actors in the sector that cut across the value chain structure of industries, often viewed as being vertical. Think employee and employer associations. The clearest example in music would be artists or musicians more broadly. They are arguably at the beginning of all the value chains (creating or being the raw material in the parlance of economics) and their approach to strategically organising their work is ideally informed by a holistic perspective – creating and taking the music to their audiences across all channels and monetising all the kinds of value they create, whether from author, performer and producer rights to live performance and the artist brand.

The political representation for segment-specific interests often finds its form through unions, alliances or forums uniting artists, authors, musicians, but also music managers. The issues these might flag can be different, or bring different perspectives to themes advocated by the industry associations.

An example can, again, be the issue of fair remuneration for artists, authors and producers from digital platforms. The producers have felt that there is a “value gap”6 between how much of digital platforms’ revenue is driven by music and the share that gets redistributed to the rights holders. The row between Universal Music and TikTok can be seen as the latest standoff in that debate. The authors (as represented by GESAC, CISAC and ECSA among others) feel, however, that compared to the ca 50-55% of digital revenues for producers, the 15-20% for authors is too little. Finally, the performers (especially non-featured artists) don’t receive anything directly from the digital platforms, only through the producers (record labels) and feel that they should also be fairly remunerated as they are from the more traditional public performance and broadcasting of recordings (background music, radio, TV, etc.). This debate sits strictly within recorded music industry value-chain and is segmented by the different actors, based on their roles, rights and past and present agreements.

Another discourse exemplifying a segment approach would be the call to clarify, perhaps even harmonise the status of artists in Europe to achieve better working conditions for artists and cultural workers.7

Music scenes

Leaving aside analytical classifications and geometrical metaphors, the concept of a music scene evokes a different perspective – one focused on music as a practice embedded in a community of music creators, performers, organisers, participants and audiences. A music scene can be focused in a particular place in a particular time – like Chicago and New York in the Jazz Age of the 1920ies, or Seattle Grunge in the early 1990ies; or it can be understood more broadly as the particular culture around certain kinds of music and practices, such as the techno, metal, folk or contemporary8 music scenes. In contrast to the sector, industry and segment perspectives, the scene lens shifts from functional definitions and highlights the cultural specificities of the scene.

There are plenty of organisations dedicated to representing the interests of particular music scenes. In Europe, various organisations for jazz, classical and traditional or global music9 is especially numerous and notable, but the picture is getting increasingly diverse. These scene-focused representative organisations, when doing their job well, are able to articulate a holistic view of the importance of certain interdependent key organisations and initiatives that are all key pieces of the puzzle. Such as education providers, big and small festivals, venues and last but not least the needs and interests of the artists and professionals working in the scene.

On the other hand, to maintain consistency of message over time, these organisations need to craft a more stable, unified and coherent picture of the scene than any reality is likely to warrant. Any music practice and style transcending a particular place and time is an abstraction and certain views of what it “really” is, what constitutes key concerns and what issues to prioritise will be more dominant in the “scene discourse” than others. Such asymmetries of power and representation are unavoidable in any kind of organisational setup. A healthy representative organisation can outwardly maintain a coherent identity and stance, while internally providing a venue for constructive debates on the most important issues.

Music ecosystem(s)

It has been suggested recently with increasing frequency that the concept of an ecosystem can be useful for making sense of the music world in revealing ways. I myself have advocated for this in several past presentations10 and there are colleagues from the Erasmus University Rotterdam that are making efforts to apply the ecosystem concept in earnest11. It is too early to dive into any practical applications and for now, the metaphoric connection to the complexity of living biosystems and the needed holistic view to nurturing them works well to pull music policy making out of its legacy ruts of binary opposition between art vs commerce, culture vs entertainment and serious vs popular. The ecosystem concept highlights the interconnectedness of all actors in the system, regardless of their (self-perceived) positions, and the challenges with overly technical policy intervention. The metaphor suggests we need to move from an engineering to nurturing mindset, including co-creative policy making. There are serious questions to be tackled to make the ecosystem lens work in practical application and this will likely remain the concern of many thinkers, writers and doers for the next few years.

What is it then? Reality and models.

There are other narratives I have not covered here at all, for example considering music as a right12 or as an art form, etc. The overarching aim of this brief tour of concepts is to underline that all of these approaches, while often used in a matter-of-fact language, as if describing the way music “is”, are simply particular perspectives. None are “natural”, all are contrived. Therefore, the question at hand is not whether music “is” a sector, a scene, or an ecosystem, nor to find an ultimate description of it as I don’t think social reality lends itself to such. Instead, we can attempt to make sense of the music world by using any or all of these particular ways of seeing and explaining to the degree they offer useful insights, while remaining critically aware of the limitations, biases and the necessarily crafted narrative consistency inherent in them. This reflexive awareness becomes important when facing the fragmentation so evident in the ways we construct political representation of music. We could ask – have we institutionalised these different perspectives to the point of crippling any holistic approach to common problems? This I will aim to tackle in my next article, so stay tuned.

John Law, “After Method. Mess in Social Science Research'' (2004, 2), but the exact phrasing is from Henrik Wagenaar, “Meaning in Action. Interpretation and dialogue in policy analysis” (2014).

The 2009 UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics, page 26.

This example is from https://www.musqetf.com/posts/growth-potential-of-the-global-music-industry, but you can easily find tens of examples across platforms of very different legitimacy.

Read Daniel Kahneman’s 2011 book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” – for this and many other reasons. It’s a great book!

This is not a criticism of IFPI. Even though I don’t know exactly how they do it, I have still used their work many times for reference. In the mostly arid desert of data about music life, their contribution is a welcome one. It’s rather a reminder that an analyst should always be alert to the quality of methodology and data.

The “value gap” term was at the centre of the discourse of the producers in the hot debates before approving the European copyright directive in 2019. It seems much less used now.

See the press release of European Parliament’s resolution on the matter from November 2023 Status of the artist: better working conditions for artists and cultural workers | News | European Parliament.

This is a troublesome term. I mean here what is often called contemporary classical music, but this is in my view an oxymoronic phrase. Adding “academic” is equally limiting as is any link to European notated historic music practices. To be tackled in some future article…

I’m picking up on the trend to not use “world music” with all its contested baggage.

Most recently together with Frank Kimenai in our keynote at the EU Conference of Music in February 2024.

For example, see this article and animation by Frank Kimenai.

See for example the “Five music rights” approach of the European Music Council, more info: https://www.emc-imc.org/about/objectives-strategies/the-5-music-rights.